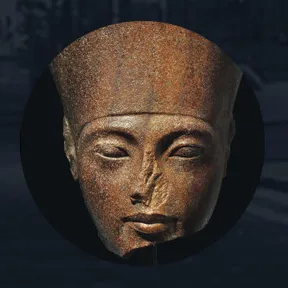

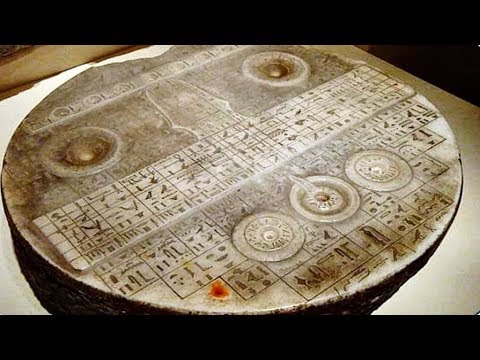

The Antikythera Mechanism

The Antikythera mechanism is an ancient Greek analogue computer and orrery used to predict astronomical positions and eclipses for calendar and astrological purposes decades in advance. It could also be used to track the four-year cycle of athletic games.

The artefact was retrieved from the sea in 1901, and identified as containing a gear wheel on 17 May 1902 by archaeologist Valerios Stais, among wreckage retrieved from a wreck off the coast of the Greek island Antikythera.

The instrument is believed to have been designed and constructed by Greek scientists and has been variously dated to about 87 BC, or between 150 and 100 BC, or to 205 BC, or to within a generation before the shipwreck, which has been dated to approximately 70-60 BC.

The device, housed in the remains of a 34 cm × 18 cm × 9 cm (13.4 in × 7.1 in × 3.5 in) wooden box, was found as one lump, later separated into three main fragments which are now divided into 82 separate fragments after conservation works.

Four of these fragments contain gears, while inscriptions are found on many others. The largest gear is approximately 14 centimetres in diameter and originally had 223 teeth.

It is a complex clockwork mechanism composed of at least 30 meshing bronze gears.

A team led by Mike Edmunds and Tony Freeth at Cardiff University used modern computer x-ray tomography and high resolution surface scanning to image inside fragments of the crust-encased mechanism and read the faintest inscriptions that once covered the outer casing of the machine.

Detailed imaging of the mechanism suggests that it had 37 gear wheels enabling it to follow the movements of the moon and the sun through the zodiac, to predict eclipses and even to model the irregular orbit of the moon, where the moon's velocity is higher in its perigee than in its apogee.

This motion was studied in the 2nd century BC by astronomer Hipparchus of Rhodes, and it is speculated that he may have been consulted in the machine's construction.

The knowledge of this technology was lost at some point in antiquity, and technological works approaching its complexity and workmanship did not appear again until the development of mechanical astronomical clocks in Europe in the fourteenth century.

All known fragments of the Antikythera mechanism are kept at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, along with a number of artistic reconstructions/replicas of how the mechanism may have looked and worked.

DISCOVERY

The Antikythera mechanism was retrieved from 45 metres (148 ft) of water in the Antikythera shipwreck off Point Glyphadia on the Greek island of Antikythera in 1901, most probably in July of that year.

The wreck had been found in April 1900 by a group of Greek sponge divers who retrieved numerous large artefacts, including bronze and marble statues, pottery, unique glassware, jewellery, coins, and the mechanism.

All were transferred to the National Museum of Archaeology in Athens for storage and analysis. The mechanism was merely a lump of corroded bronze and wood at the time and went unnoticed for two years, while museum staff worked on piecing together more obvious statues.

On 17 May 1902, archaeologist Valerios Stais found that one of the pieces of rock had a gear wheel embedded in it. He initially believed that it was an astronomical clock, but most scholars considered the device to be prochronistic, too complex to have been constructed during the same period as the other pieces that had been discovered.

Investigations into the object were dropped until British science historian and Yale University professor Derek J. de Solla Price became interested in it in 1951. In 1971,

Price and Greek nuclear physicist Charalampos Karakalos made X-ray and gamma-ray images of the 82 fragments. Price published an extensive 70-page paper on their findings in 1974.

It is not known how the mechanism came to be on the cargo ship, but it has been suggested that it was being taken from Rhodes to Rome, together with other looted treasure, to support a triumphal parade being staged by Julius Caesar.

Two other searches for items at the Antikythera wreck site in 2012 and 2015 have yielded a number of fascinating art objects and a second ship which may or may not be connected with the treasure ship on which the Mechanism was found.

Also found was a bronze disk, with the image of a bull embellished on it. The disk has four "ears" which have holes in them, and it was thought by some that it may have been part of the Antikythera Mechanism itself, as a "cog wheel".

However, there appears to be little evidence that it was part of the Mechanism; it is more likely that the disk was a bronze decoration on a piece of furniture.

ORIGIN

The Antikythera mechanism is generally referred to as the first known analogue computer. The quality and complexity of the mechanism's manufacture suggests that it has undiscovered predecessors made during the Hellenistic period.

Its construction relied on theories of astronomy and mathematics developed by Greek astronomers during the second century BC, and it is estimated to have been built in the late second century BC or the early first century BC.

In 1974, Derek de Solla Price concluded from gear settings and inscriptions on the mechanism's faces that it was made about 87 BC and lost only a few years later. Jacques Cousteau and associates visited the wreck in 1976 and recovered coins dated between 76 and 67 BC.

The mechanism's advanced state of corrosion has made it impossible to perform an accurate compositional analysis, but it is believed that the device was made of a low-tin bronze alloy (of approximately 95% copper, 5% tin). Its instructions were composed in Koine Greek.

In 2008, continued research by the Antikythera Mechanism Research Project suggested that the concept for the mechanism may have originated in the colonies of Corinth, since they identified the calendar on the Metonic Spiral as coming from Corinth or one of its colonies in Northwest Greece or Sicily.

Syracuse was a colony of Corinth and the home of Archimedes, and the Antikythera Mechanism Research project argued in 2008 that it might imply a connection with the school of Archimedes.

However, it has recently been demonstrated that the calendar on the Metonic Spiral is indeed of the Corinthian type but cannot be that of Syracuse.

Another theory suggests that coins found by Jacques Cousteau at the wreck site in the 1970s date to the time of the device's construction, and posits that its origin may have been from the ancient Greek city of Pergamon, home of the Library of Pergamum.

With its many scrolls of art and science, it was second in importance only to the Library of Alexandria during the Hellenistic period.

The ship carrying the device also contained vases in the Rhodian style, leading to a hypothesis that it was constructed at an academy founded by Stoic philosopher Posidonius on that Greek island.

Rhodes was a busy trading port in antiquity and a centre of astronomy and mechanical engineering, home to astronomer Hipparchus who was active from about 140 BC to 120 BC.

The mechanism uses Hipparchus's theory for the motion of the moon, which suggests the possibility that he may have designed it or at least worked on it. In addition, it has recently been argued that the astronomical events on the Parapegma of the Antikythera Mechanism work best for latitudes in the range of 33.3–37.0 degrees north, the island of Rhodes is located between the latitudes of 35.85 and 36.50 degrees north.

In 2014, a study by Carman and Evans argued for a new dating of approximately 200 BC based on identifying the start-up date on the Saros Dial as the astronomical lunar month that began shortly after the new moon of 28 April 205 BC.

Moreover, according to Carman and Evans, the Babylonian arithmetic style of prediction fits much better with the device's predictive models than the traditional Greek trigonometric style.

A study by Paul Iversen published in 2017 reasons that the prototype for the device was indeed from Rhodes, but that this particular model was modified for a client from Epirus in northwestern Greece, and was probably constructed within a generation of the shipwreck.

Further dives were undertaken in 2014, with plans to continue in 2015, in the hope of discovering more of the mechanism.

A Greek shipwreck holds the remains of an intricate bronze machine that turns out to be the world's first computer. In 1900, a storm blew a boatload of sponge divers off course and forced them to take shelter by the tiny Mediterranean island of Antikythera.

Diving the next day, they discovered a 2,000 year-old Greek shipwreck. Among the ship's cargo they hauled up was an unimpressive green lump of corroded bronze.

Rusted remnants of gear wheels could be seen on its surface, suggesting some kind of intricate mechanism. The first X-ray studies confirmed that idea, but how it worked and what it was for puzzled scientists for decades.

Recently, hi-tech imaging has revealed the extraordinary truth: this unique clockwork machine was the world's first computer.

An array of 30 intricate bronze gear wheels, originally housed in a shoebox-size wooden case, was designed to predict the dates of lunar and solar eclipses, track the Moon's subtle motions through the sky, and calculate the dates of significant events such as the Olympic Games.

No device of comparable technological sophistication is known from anywhere in the world for at least another 1,000 years. So who was the genius inventor behind it?

And what happened to the advanced astronomical and engineering knowledge of its makers? NOVA follows the ingenious sleuthing that finally decoded the truth behind the amazing ancient Greek computer.

The Antikythera mechanism was designed to predict movements of the sun, moon and planets.

The artifact was recovered probably in July 1901 from the Antikythera shipwreck off the Greek island of Antikythera. Believed to have been designed and constructed by Greek scientists, the instrument has been dated either between 150 and 100 BC, or, according to a more recent view, in 205 BC.

After the knowledge of this technology was lost at some point in antiquity, technological artefacts approaching its complexity and workmanship did not appear again until the development of mechanical astronomical clocks in Europe in the fourteenth century.

All known fragments of the Antikythera mechanism are kept at the National Archaeological Museum, in Athens, along with a number of artistic reconstructions of how the mechanism may have looked.

Generally referred to as the first known analogue computer, the quality and complexity of the mechanism's manufacture suggests it has undiscovered predecessors made during the Hellenistic period. Its construction relied upon theories of astronomy and mathematics developed by Greek astronomers, and is estimated to have been created around the late second century BC.

In 1974, Derek de Solla Price concluded from gear settings and inscriptions on the mechanism's faces that it was made about 87 BC and lost only a few years later. Jacques Cousteau and associates visited the wreck in 1976 and recovered coins dated to between 76 and 67 BC.

Though its advanced state of corrosion has made it impossible to perform an accurate compositional analysis, it is believed the device was made of a low-tin bronze alloy (of approximately 95% copper, 5% tin). All its instructions are written in Koine Greek, and the consensus among scholars is that the mechanism was made in the Greek-speaking world.