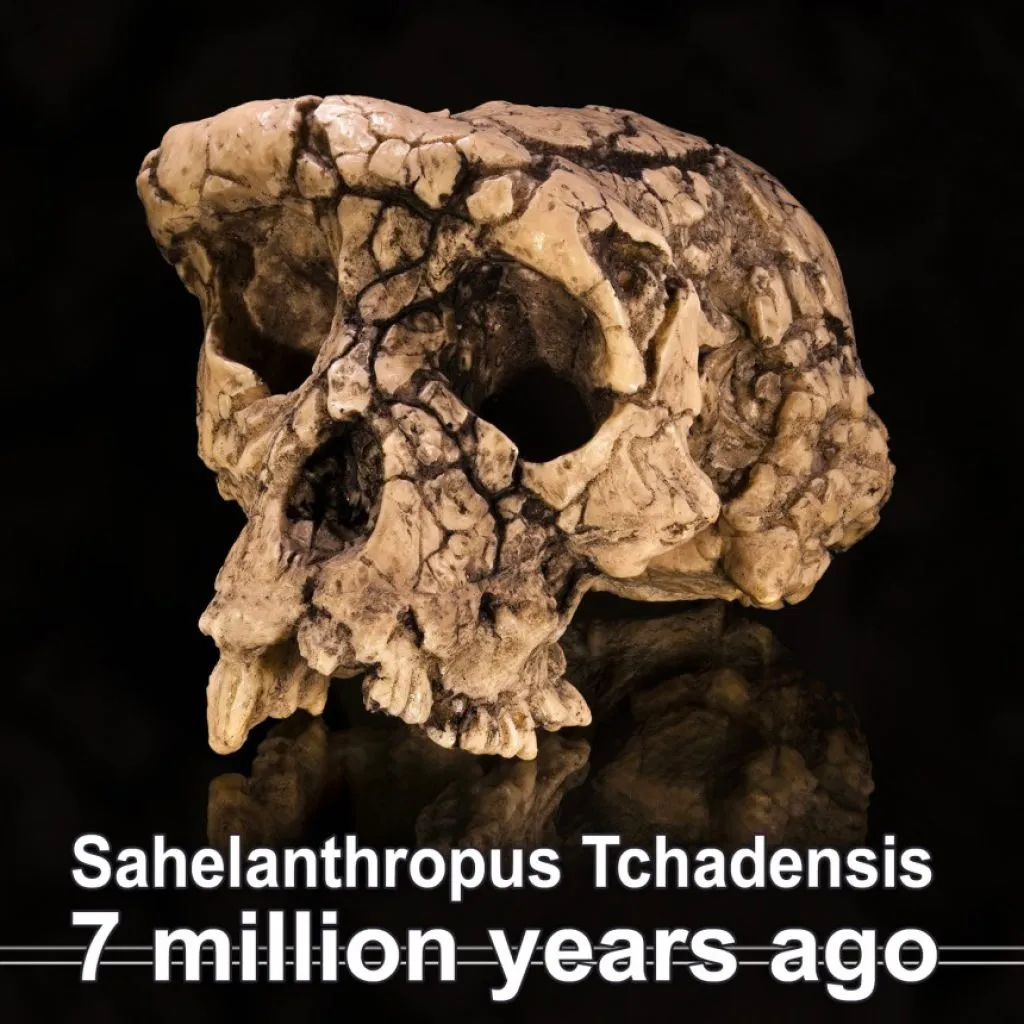

Sahelanthropus Tchadensis

Sahelanthropus tchadensis is an extinct Hominini species and is probably the ancestor to Orrorin that is dated to about 7 million years ago, during the Miocene epoch, possibly very close to the time of the chimpanzee–human divergence.

Few specimens other than the partial skull nicknamed Toumaï ("hope of life") are known. Sahelanthoropus Tchadensis, described in 2002, was found in Chad, far away from the East African Rift Valley and South Africa, where the search for early hominins had previously been concentrated.

Existing fossils include a relatively small cranium named Toumaï ("hope of life" in the local Daza language of Chad in central Africa), five pieces of jaw, and some teeth, making up a head that has a mixture of derived and primitive features. The braincase, being only 320 cm3 to 380 cm3 in volume, is similar to that of extant chimpanzees and is notably less than the approximate human volume of 1350 cm3.

The teeth, brow ridges, and facial structure differ markedly from those found in Homo sapiens. Cranial features show a flatter face, u-shaped dental arcade, small canines, an anterior foramen magnum, and heavy brow ridges. No postcranial remains have been recovered. The only known skull suffered a large amount of distortion during the time of fossilisation and discovery, as the cranium is dorsoventrally flattened, and the right side is depressed.

Sahelanthropus tchadensis may have walked on two legs. However, because no postcranial remains (i.e., bones below the skull) have been discovered, it is not known definitively whether Sahelanthropus was indeed bipedal, although claims for an anteriorly placed foramen magnum suggests that this may have been the case. Upon examination of the foramen magnum in the primary study, the lead author speculated that a bipedal gait "would not be unreasonable" based on basicranial morphology similar to more recent hominins. Some palaeontologists have disputed this interpretation, stating that the basicranium, as well as dentition and facial features, do not represent adaptations unique to the hominin clade, nor indicative of bipedalism;[4] and stating that canine wear is similar to other Miocene apes. Further, according to recent information, what might be a femur of a hominid was also discovered near the cranium—but which has not been published nor accounted for.

RELATIONSHIP TO HUMANS AND CHIMPANZEES

Sahelanthropus may represent a common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees, though no consensus has been reached yet by the scientific community. Sahelanthropus has several features in common with later hominins such as Kenyanthropus and Homo. The canines are relatively small and show wear at their tips, and the tooth enamel is thicker than is seen in apes. The face is also quite flat compared with apes, and the brow ridge is massive and continuous above the orbits. In many other respects, however, Sahelanthropus does resemble living and extinct apes. The cranial capacity is small, and the shape of the rear part of the skull is a truncated triangle. It has been argued that because Sahelanthropus presents this mosaic of primitive and recently evolved characteristics, it probably should be placed on the human family tree close to the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees. The original placement of this species as a human ancestor but not a chimpanzee ancestor would complicate the picture of human phylogeny. In particular, if Toumaï is indeed a direct human ancestor, then its facial features bring into doubt the status of Australopithecus whose thickened brow ridges were reported to be similar to those of some later fossil hominins (notably Homo erectus), and where the brow ridge morphology of Sahelanthropus differs from that observed in all australopithecines, most fossil hominins and extant humans.

Another possibility is that Toumaï is related to both humans and chimpanzees, but is the ancestor of neither. Brigitte Senut and Martin Pickford, the discoverers of Orrorin tugenensis, suggested that the features of S. tchadensis are consistent with a female proto-gorilla. Even if this claim is upheld the find would lose none of its significance, because at present, very few chimpanzee or gorilla ancestors have been found anywhere in Africa. Thus if S. tchadensis is an ancestral relative of the chimpanzees or gorillas, then it represents the earliest known member of their lineage. And S. tchadensis does indicate that the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees is unlikely to closely resemble extant chimpanzees, as had been previously supposed by some paleontologists.

A further possibility, highlighted by research published in 2012, is that the human–chimpanzee split is earlier than previously thought, with a possible range of 7 to 13 million years ago (with the more recent end of this range being favoured by most researchers), based on slower than previously thought changes between generations in human DNA. Indeed, some researchers (such as Tim D. White, University of California) consider suggestions that Sahelanthropus is too early to be a human ancestor to have evaporated.

Sediment isotope analysis of cosmogenic atoms in the fossil yielded an age of about 7 million years. In this case, however, the fossils were found exposed in loose sand; co-discoverer Beauvilain cautions that such sediment can be easily moved by the wind, unlike packed earth, making the date of 7 million years less certain.

In fact, Toumaï may have been reburied in the recent past. Taphonomic analysis reveals the likelihood of one, perhaps two, burial(s). Two other hominid fossils (a left femur and a mandible) were in the same "grave" along with various mammal remains. The sediment surrounding the fossils might thus not be the material in which the bones were originally deposited, making it necessary to corroborate the fossil's age by some other means. The fauna found at the site – namely the anthracotheriid Libycosaurus petrochii and the suid Nyanzachoerus syrticus – suggests an age of more than 6 million years, as these species were probably already extinct by that time.